Last year was a big year for age verification and assurance policies: the US Supreme Court upheld a Texas law mandating age verification for obscene, sexual content, setting a lower legal standard of protection for sexual expression, and other states took a similar approach. The UK’s Online Safety Act went into effect, creating a widespread regulation of social media companies, requiring them to restrict various forms of “harmful” online content unless a user verifies their age. Even more drastically, Australia banned kids under the age of 16 from having social media accounts on large platforms.

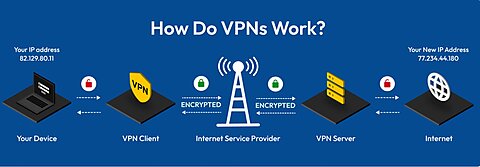

But as these restrictions on various types of online content grow, a major challenge quickly emerges—how to prevent users from circumventing them, especially with Virtual Private Networks (VPNs). When states like Texas, Mississippi, or California, or nations like the UK or Australia, demand that online platforms conduct age verification checks in their jurisdictions, they are relying on platforms to determine when a user is based in that region. While IP addresses do not directly provide geolocation data, they are publicly registered and associated with Internet Service Providers. So an IP address can generally be traced back to a major city, state, or nation with reasonable accuracy.

The most direct challenge to such geolocation is a VPN. VPNs work by routing users’ web traffic through the servers of the VPN operator. This process not only encrypts the users’ web traffic but also hides their IP addresses, instead showing them originating from the location of the VPN servers. So, for example, a user in Australia might use a VPN server in New York City. When they go to access a platform like Instagram or X that Australian law demands be subject to age restrictions, the platform looks to see if the user is from Australia, but their IP address shows as being from New York. As such, the platform has no reason to conduct an age verification check, and Australians are able to access the platform without age verification.

Obviously, this is a pretty major gap in the defense of age-verification and assurance regimes. Even if they could securely, correctly, and consistently conduct age checks (which they can’t), none of that matters if users can avoid the checks by appearing to be from a different location. It should come as no surprise, then, that each place where age verification policies have gone into effect has seen a surge in VPN usage.

It is also worth noting that not all VPNs are created equal. While many respected VPNs provide significant security and privacy benefits that come along with encrypting and disguising your web traffic, less effective or poor VPNs could actually create security risks. As such, age verification regimes may push users toward VPNs that obscure location but are actually worse for privacy and security. Regardless, VPNs create a significant loophole in age verification regimes.

One result has been policymakers increasingly threatening VPNs. In the UK, the House of Lords voted to ban VPNs for those under 18 (as well as an Australia-style social media ban for those under 16), demanding that VPNs themselves age-gate their services, with other government officials supporting VPN restrictions. In Australia, the guidance issued by the eSafey Commission expects platforms “to try to stop users from using VPNs to pretend to be outside Australia.” What that means in practice is that platforms are expected to look for other indicators of location, such as cell phone or device numbers, pictures, or statements of being in Australia, etc.

But, while it’s true such measures can crack down on VPN usage, the government holds the power to further punish platforms if it believes they have not done enough to stop the use of VPNs. In the US, state policymakers proposed that age-verification laws for online adult content in Wisconsin would require platforms to block any users using a VPN. Michigan would go even further, demanding Internet Service Providers detect and block VPN usage broadly.

Threatening VPNs means threatening important privacy and security tools for a host of users. Businesses, universities, and travelers on the go frequently use VPNs to secure their communications and access their organization’s systems. Those in need of privacy, such as activists and journalists, or those fleeing violent or dangerous situations, all may make use of VPNs to keep themselves safe. And the type of countries that ban (e.g., North Korea, Belarus, Turkmenistan) or restrict and control VPN usage (e.g., China, Russia, Turkey, Iran) should make it clear that authoritarians appreciate the threat that VPNs pose to their rule. Restricting VPNs does not support expression and privacy but rather harms them.

The point is that when an internet policy can be avoided by a relatively common technology that often provides significant privacy and security benefits, maybe the policy is the problem. Age verification regimes do plenty of damage to online speech and privacy, but attacking VPNs to try to keep them from being circumvented is doubling down on this damaging approach.

Rather than viewing VPNs as a threat (as authoritarian governments around the world do), American policymakers must instead respect and protect the privacy, security, and expression of their citizens by protecting their access to technologies like VPNs and online platforms.