Last May, I wrote a piece called “We Are Measuring Inflation All Wrong: Non‐housing Inflation Is Very Low.” That has not changed. The uniquely quirky way “shelter” costs are estimated by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics commands such a huge share of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) that it has overwhelmed everything else for nearly two years.

This is mostly due to “Owners’ Equivalent Rent” (OER) which accounts for an astonishing 26.8 percent of the CPI. Rent accounts for another 7.7 percent of the CPI, and hotels for 1 percent.

Owners’ equivalent rent purports to measure monthly variations in a price nobody pays, and to average those estimates for every house in the entire country. Nearly every other country wisely excludes such impossibly arbitrary OER estimates from their measure of inflation. Yet that singular made‐up number dominates the US CPI, and to a lesser extent the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) inflation index too.

Shelter accounts for 36.1 percent of the CPI and 42 percent of Core CPI. Shelter also accounts for 60 percent of measured inflation in non‐energy services. This turns out to matter quite a lot, because estimated inflation for shelter has long been extremely high, while inflation for everything else has been extremely low.

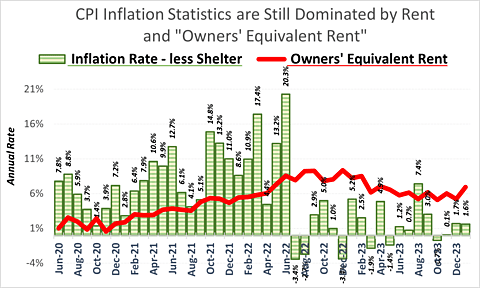

The Graph shows that from July 2022 to January 2024, the average CPI inflation rate for shelter was 7 percent, yet the average inflation rate for everything else was only 1.2 percent. This January alone, the reported annual inflation rate for shelter was 6.9 percent, but inflation for everything else was 1.6 percent.

When the January CPI came out, Wall Street Journal reporters Justin Lahart and Nick Timiraos opined that, “Inflation eased again in January but came in above Wall Street’s expectations, clouding the Federal Reserve’s path to rate cuts and potentially giving the central bank breathing space to wait until the middle of the year.” That implied the Federal Open Market Committee might base the next few months’ interest rate manipulations on one month’s “unexpected” OER surge. It also implies that the Fed somehow imagines that keeping the interest rate on bank reserves far above the non‐housing inflation rate could, in some inexplicable way, diminish future increases in rents.

Federal Reserve apologists prefer to naively accept such official shelter inflation statistics on faith — ostensibly believing that typical market rents have actually been rising at a 7 percent annual rate nationwide— rather than to even consider the possibility that the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has no idea how to estimate a national average of rents, much less an average of what all houses everywhere might rent for.

We know that is not true because the BLS now collects information about repeat rents for new tenants on the same housing units. The second graph shows that the BLS New Tenant Rent Index was much lower in the fourth quarter of 2023 than it was a year earlier.

If the U.S. measured consumer prices in the same “harmonized” way other countries do —by simply excluding dubious guesstimates of Owners’ Equivalent Rent— the average rate of inflation was 2.3 percent over the past twelve months, 1.1 percent over the past six, and zero over the past three.